It's Friday and you're speeding 5 miles over, anxious to get to your favorite brewery. A glimmer of light flashes across your rearview mirror: those familiar blue and red lights of your local police officer, doing his routine gig. The officer notices you're tight lipped and testy — or maybe too smiley and sweaty — and decides to search your car.

He finds three Adderall pills and a 1/2-gram baggie of cocaine. You're now a convicted felon, facing up to 20 years in prison, lumped in with those serving life sentences for murder and armed robberies.

Is this a film? No.

Is this over-exaggerated?

It depends.

25seconds. That's how often an American is arrested for drug possession — usually for small "user" quantities — with police making these arrests more often than any other crime. In Oregon, African Americans make up only 2 percent of the total population, but they account for 9 percent of all inmates in state prison. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission found that the current rate of incarceration for black people is 5.6 times higher than that of white people. Equally staggering are the numbers for Native Americans — convicted of drug possession at five times the rate of people of European descent.

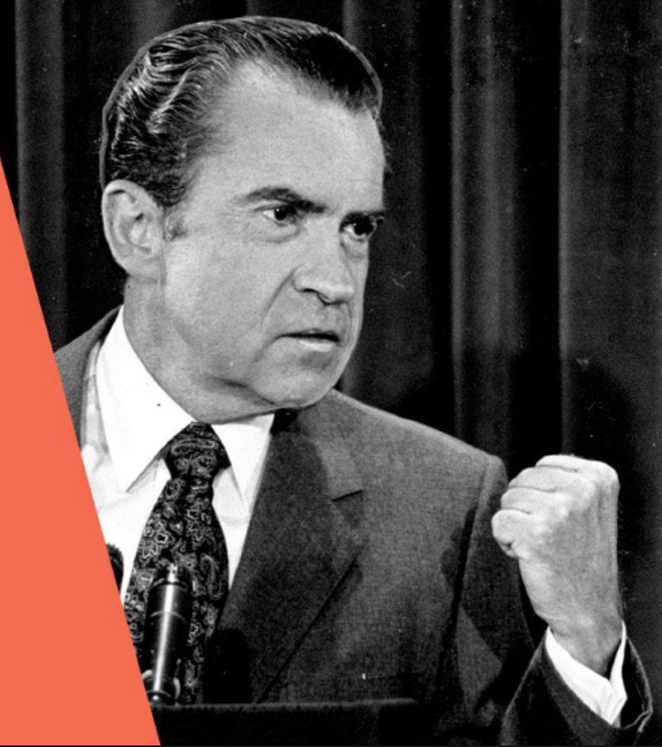

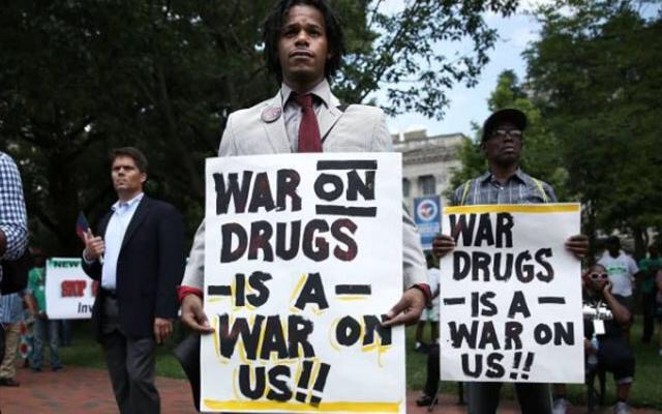

Unequal conviction and incarceration rates for minorities in Oregon are the fallout of the "War on Drugs" propaganda peddled throughout the past few decades. Drug laws are often touted by officials to suppress illegal drug trafficking, but a 2016 report by the American Civil Liberties Union noted that the rate of people arrested for possessing drugs is substantially higher than those caught selling them — four times higher.

Human Rights Watch and the ACLU, in their joint 196-page report, "Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States," showcase that small quantity drug possession amounts to 1.2 million arrests annually, resulting in 137,000 men and women currently behind bars. As most face stiff felony sentences — a felony carries a penalty of up to 20 years — each day, tens of thousands are convicted for crimes not unlike what a large-scale drug trafficker would face, but for much smaller crimes.

Many convicted of minor crimes will cycle through prisons and spend their lives on probation and/or parole, often burdened with crippling debt, all the while still struggling, in many cases, with a drug addiction. Stifled with stigma and discrimination, entire communities and taxpayers suffer the impacts.

The War On Drugs Isn't Working

On July 6, Oregon joined 16 other states in reclassifying the possession of six "hard" drugs. The State Senate passed HB 2355, effectively "de-felonizing" those caught with small amounts of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and other Schedule I and II drugs. Offenders found with these small user-amounts will now face lessened fines and reduced incarceration time—provided they have had no more than two previous drug convictions.

Currently, possession of the "harder" drugs is a Class B or Class C felony — depending on the drug — punishable by up to either 10 or 20 years in prison and up to $250,000 or $375,000 in fines. The bill — now awaiting a signature from Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, who has indicated her support— will reclassify the offenses to a Class A misdemeanor, punishable by up to one year in jail and a $6,250 fine. People caught with "substantial quantities" of illicit drugs would still face felony possession charges.

Reducing mass incarceration, expanding access to drug treatment and eradicating racial profiling are the primary goals of the bill. Oregon lawmakers said they hope to encourage medical help rather than filling up state prisons as the opioid epidemic grows to the second highest rate of addiction in the country, according to The Oregon Medical Association.

Presently, those caught with even trace amounts of illegal drugs — such as the residue left on a pipe —can theoretically be convicted of felony drug possession. According to the ACLU, as many as 1,500 Oregonians are saddled with their first drug conviction each year, amounting to a felony, with 500 of these new felons never having any prior criminal record. Felonies are often deemed the most violent and serious of crimes and include offenses such as murder, arson, fraud, and armed robbery, and are therefore permanently on a person's record. This greatly reduces chances of finding stable housing or employment.

We don't like to look at the disparity in our prison system.

It is institutional racism. ... We can pretend it doesn't exist, but it does."

— Sen. Jackie Winters

"This is an incredibly, incredibly important bill," said Democratic House Speaker Tina Kotek. "It represents the next step of Oregon's surety to making sure individuals and communities across the state, including Oregonians of color, feel fairly represented and have good interactions with law enforcement." Kotek spoke about the importance of coupling an anti-profiling law with official data, so "that officials know what to do with the results." In an effort to understand racial disparity within Oregon, the bill makes data collection mandatory from all traffic and pedestrian stops officers make.

Demographics collected will include age, race and gender. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission will use the data to analyze the demographic data police departments collect and will notify them of any disparities, so that departments can make adjustments to their current practices. In the past, minorities have been recorded as facing criminal charges for minor infractions such as jay-walking or littering.

"The war on drugs has failed," said David Rogers, executive director of the ACLU of Oregon. "It has damaged families and cost taxpayers billions of dollars. A felony conviction for small-scale drug use is too harsh because it ruins people's lives. Oregonians are ready for a smarter approach."

So Go Out and Toke, Right?

To be clear, we are not encouraging people to go out and use drugs," wrote Tess Borden, 2015-2017 Aryeh Neier Fellow at ACLU and HRW, and the primary author of the published report. "What we are saying is that people shouldn't be arrested, prosecuted and potentially incarcerated — and saddled with all the consequences of a criminal record — for personal drug use, i.e. decisions about what they put in their own bodies."

Borden used countless examples to illustrate the disconnect between local and state governments in dealing with small-use possession. In one case, a man faced 20 years for being in the backseat of a truck that had a 1/2-gram quantity of a controlled substance. The man received a three-year sentence.

Borden emphasized that felons often spend time socializing with criminals who are in prison for more serious charges and that, in fact, many criminals charged with homicide get out in less than 20 years. Cases such as these are countless across the state and the report says they have "yielded few, if any, benefits.... Criminalizing drugs is not an effective public safety policy. We are aware of no empirical evidence that low-level drug possession defendants would otherwise go on to commit violent crimes."

If defendants do commit additional crimes, advocates such as the ACLU and Borden say those charges should be prosecuted in the same way as if they were done while intoxicated with alcohol—another substance that at one time was prohibited. Borden also noted the financial implications. "The enormous resources spent to identify, arrest, prosecute, sentence, incarcerate and supervise people whose only offense has been possession of drugs is hardly money well spent...and it has caused far more harm than good."

Oregon Progressing Forward to Eliminate Profiling

Our Legislature's decision to decriminalize small amounts of drugs and expand access to treatment is an important step forward in ending the disastrous drug war," said former prosecutor and Law Enforcement Action Partnership board member Inge Fryklund. "The harm reduction approach can help address the underlying problems that lead to addiction and keep people who pose little public safety threat out of the justice system." LEAP is a nonprofit group that advocates for criminal justice reforms and drug policies, made up of police, prosecutors, judges and other criminal justice professionals. They were staunch supporters of the bill that was chaired by Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum.

"Our Task Force traveled throughout the state listening to Oregonians sharing their experiences with profiling," said Rosenblum. "The stories we heard were profoundly important and deeply impactful." House members heard testimonies from community members about their racial profiling experiences. Linda Hamilton was one such case, who retold being pulled over in a traffic stop allegedly because she's black. Hamilton is a Lane County parole and probation officer.

The Hispanic community also came forward with accounts of profiling, with University of Oregon student Maria Gallego testifying that her partner now has Post Traumatic Stress Disorder from an encounter with law enforcement. Testimonies like these were what Democrats said would help be the building blocks to form a bridge between police and communities of color.

Although strongly favored by most Democrats, some Republicans, such as Rep. Andy Olson voted against the bill, saying "I fully support the collection of data to monitor racial profiling, but I am opposed to reducing drug classification." Sen. Betsy Johnson, a Democrat, also voted against it in the Senate, arguing that it was a "hug-a-thug" policy. Both local House members, Rep. Knute Buehler and Rep. Gene Whisnant, voted no. Sen. Tim Knopp abstained from the vote in the Senate.

Sen. Jackie Winters — the longest serving African-American woman in the Oregon Senate, and a Republican — was a strong advocate for the bill and pushed back on Johnson's stance, noting in the Ways and Mean Committee that, "There is empirical evidence that there are certain things that follow race. ... We don't like to look at the disparity in our prison system," Winters said. "It is institutional racism. ... We can pretend it doesn't exist, but it does."

Democrat Mitch Greenlick said, "We've got to treat people, not put them in prison. It would be like putting them in the state penitentiary for having diabetes... This is a chronic brain disorder and it needs to be treated this way."

The Oregon Association Chiefs of Police also wrote a letter in support of the bill. "Too often, individuals with addiction issues find their way to the doorstep of the criminal justice system when they are arrested for possession of a controlled substance," wrote Kevin Campbell, the executive director. "Unfortunately, felony convictions in these cases also include unintended and collateral consequences including barriers to housing and employment and a disparate impact on minority communities."

The bill is seen as an addition to the 2015 law that made Oregon the 31st state to prohibit racial profiling. However, it did not provide guidance for dealing with the issue. Recording mandatory data is seen as a progressive step in implementing this law.

What now?

Officer training to prevent unlawful police profiling and overcoming any biases is the first step police departments will undertake with this new legislation. It will also protect lawful immigrants from facing mandatory deportation for low level, nonviolent offenses and advocate for treatment rather than prison time.

In an interview with the Washington Post, Winters said, "We can't continue on the path of building more prisons when often the underlying root cause of the crime is substance use." With the opioid crisis in effect, states are changing tactics from one of criminality to a public health concern. "We are trying to move policy towards treatment rather than prison beds."

With many Oregon counties in support — Deschutes County was in favor of the bill — of already implementing drug diversion programs, the hope is to expand programs to rural and lower-income countries that generally don't have the beds available for treatment. The state will provide local jurisdictions with $7 million to implement drug diversion programs.

As the bill awaits Gov. Brown's signature, she released a statement indicating her support. "HB 2355 represents an important step towards creating a more equitable justice system to better serve all Oregonians...Addressing disparities that too often fall along racial and socioeconomic lines should not be political issues. Here in Oregon, we're demonstrating that we can make meaningful progress to improve the lives of Oregonians by working together around our shared values."